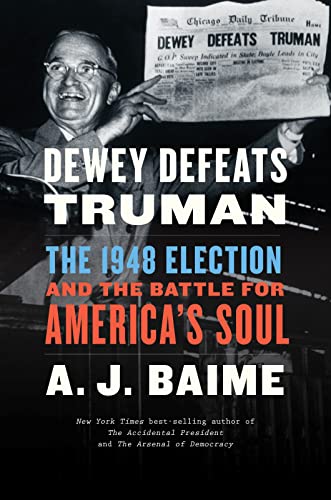

Dewey Defeats Truman: The 1948 Election and the Battle for America's Soul

“Dewey Defeats Truman, A. J. Baime’s lively and insightful account of the second-most shocking presidential upset in modern history, delivers the best-reasoned and most revealing examination to date of that memorable mid-century election.”

Dewey Defeats Truman, A. J. Baime’s lively and insightful account of the second-most shocking presidential upset in modern history, delivers the best-reasoned and most revealing examination to date of that memorable mid-century election.

The book takes its title from the most famously bungled front-page headline of a major newspaper in the 20th century. The Chicago Daily Tribune, like virtually every news outlet in the country, considered Republican challenger Thomas E. Dewey’s victory over embattled incumbent Harry S. Truman such a foregone conclusion that it completed its post-election coverage well before the votes were counted, printing 150,000 copies of the paper’s morning edition declaring Dewey’s landslide victory. The Tribune’s gaffe also yielded a timeless photograph of the victorious, grinning Truman posing with the paper on the back of his campaign railcar, the post from which he had delivered hundreds of rousing, extemporaneous speeches that had captivated rural America and vaulted him to victory.

As Baime writes, “More Americans today are likely familiar with the phrase Dewey Defeats Truman than they are with Thomas E. Dewey. If Americans know of Thomas Dewey, it is mostly because he lost to Harry Truman in 1948.”

Baime’s book arrives three and a half years after the 2016 election result that proved even more confounding than 1948’s, and in the heat of a new presidential race that no amount of lopsided polling could make a properly chastened prognosticator call prematurely. Baime’s book also appears hot on the heels of a handful of books that bring one or another aspect of Truman’s complex presidency vividly to life.

The obvious antecedent to Dewey Defeats Truman is Baime’s own The Accidental President (2017), which applies the author’s signature gift for gripping historical narrative to Truman’s tumultuous first four months in office following Franklin Roosevelt’s sudden death. Those 120 days proved as intense a trial by fire as any president has had. On his 82nd day as a little-known or admired vice president, Truman was called to fill the shoes of a man who had redefined the role of the federal government and reshaped the world, to steer war in two theaters toward unconditional surrender, to learn of the existence of the most destructive weapon in human history, and confront the awful knowledge that the decision to use it would fall to him alone.

As Truman biographer David McCullough writes, “To many it was not just that the greatest of men had fallen, but that the least of men—or at any rate the least likely of men—had assumed his place.”

Two indispensable recent books have examined the origins and consequences of Truman’s late conversion to African American legal (if not social) equality, in particular events that inspired and surrounded the president’s July 1948 Executive Order 9981 calling for desegregation of the United States military. James Rawn Jr.’s sweeping The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America’s Military appeared in 2013; Richard Gergel’s revelatory Unexampled Courage: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring was published last year. To Harry Truman, scion of an unreconstructed Southern family, Isaac Woodard was George Floyd—tip of an iceberg of longstanding, ongoing state-sanctioned white terrorism. But Woodard’s disfiguring abuse at the hands of local authorities awakened Truman’s conscience, and proved a tipping point in bringing a long-overdue measure of justice to African Americans.

Late 2016 also brought The General vs. The President from the eminent narrative historian H. W. Brands. The book plumbs Truman’s protracted battle for dominion over Korean War objectives with a far tougher foe than he faced in 1948: General Douglas MacArthur. Among other things, the book reminds readers that MacArthur stood unsurpassed in his military genius, his disdain for civilian authority, his preening self-regard, and his penchant for blaming anyone but himself for his own failures.

The recent book that most closely parallels Baime’s Dewey Defeats Truman is David Pietrusza’s 1948. Pietrusza’s book, like Baime’s, zooms in on the 1948 election, narrating in gripping detail all its dramatic and unlikely twists and turns.

As one might expect, the two books cover much of the same ground, beginning with backstories of the election's four candidates: unelected incumbent Truman, the Democratic nominee; New York governor Dewey, the Republican nominee and overwhelming odds-on favorite; former Democratic Vice President Henry Wallace, the Progressive Party candidate; and South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond, representing mutinous Dixiecrats’ breakaway States’ Rights Party.

Both books chronicle the Democratic Party splits that made it a four-way race, the discordant conventions carried out for the first time under hot and unflattering lights for TV broadcast, the strikingly unprophetic polls and myopic campaign reporting, the backdrop of escalating tensions in the divided city of Berlin and the fledgling state of Israel, the candidates’ assorted misadventures on the campaign trail, and true oddities like Truman’s misbegotten plan to send Supreme Court Chief Justice Fred Vinson on a pre-election junket to the Soviet Union, and the humiliating unearthing of Wallace’s nutball “Guru Letters.”

Pietrusza spins a compelling tale that provides a convincing explanation of why Dewey lost, but arguably doesn’t do enough to explain why Truman won. In describing how Truman overcame the universal doubts of the chattering classes to pull off a victory that no one believed possible (except for Truman himself and DNC associate director India Edwards), it seems a stretch to do so with acknowledging that the Truman did more than a few things right. Pietrusza credits Truman for competently executing a few well calculated strategic gimmicks, but little more.

In Pietrusza’s telling, the real story was not so much Truman’s monumental effort to win as Dewey’s lackluster strategy of playing not to lose. With stump speeches consisting of equal parts “schmaltz and vitriol,” Pietrusza writes, “Truman had emerged, quite improbably, ‘the best barker for his own show.’ . . . Harry Truman was very, very lucky that his Republican critics were hardly their own best pitchmen.”

Baime gives more credit where credit was due, and in doing so more effectively unravels the mystery of how Truman’s stunning upset came about. Truman began his comeback by shocking Democratic Convention delegates out of the doldrums of inevitable defeat with a rousing indictment of the Republican-majority 80th Congress—a stupendously obstructionist, savagely anti-labor, staunchly do-nothing bunch that had blocked Truman’s domestic agenda at every turn.

There, Truman alit on an incontrovertible truth: The Republican Party of 1948 stood at cross-purposes with itself. Its presidential nominee, Thomas E. Dewey, had departed the Republican convention with an approved platform as liberal as Truman’s own, while a congressional majority led by the conservative Robert Taft had spent the last two years delighting in its power to crush virtually the same agenda as advanced by Truman. The chronically underestimated president realized he could drive a stake through the GOP and expose its resistance to its own purported platform by calling congress into an emergency session to take up the liberal domestic agenda that the majority party’s own national convention had just endorsed.

When Truman revived the DNC crowd with this declaration, Baime writes, “The roar of approval was so loud it was a full thirty seconds before Truman could get another word in.”

Truman then commissioned a Pullman railcar called the Ferdinand Magellan that would cover more than 31,000 miles criss-crossing the country over the next four months, with Truman speaking to improbably large crowds at whistlestops from coast to coast. That part of the Truman legend is well known, as is the shoestring nature of his perpetually underfunded campaign.

But what propelled Truman’s campaign forward, as Baime reveals, was not just mileage and message, but data. The DNC established a secret research division that fed the candidate facts and talking points tailored to match the interests of voters at each stop on his breakneck journey.

In Whistle Stop (2014), which provides a vigorous account of Truman’s campaign tour, Philip White paints a vivid picture of the candidate’s indispensable fact tank: “Holed up in a noisy, airless office in Washington’s Dupont Circle by day and the insect-plagued American Veterans Committee boarding house by night, the Research Division provided a localized fact sheet for every single stop.”

Truman came out fighting at every opportunity, his lack of formal education and his small-town, plainspoken but feisty, everyman persona—not to mention his practical need to speak off the cuff because he was too blind to read a speech with any feeling—finally became assets instead of liabilities. Baime explains, “The only shot he had was to put on a campaign so surprising, it would take the nation by storm.” That it did.

Dewey took precisely the opposite approach: “The way Dewey saw it, he had this election won; all he had to do was refrain from making mistakes or painting himself as reactionary,” Baime writes. “Dewey’s closest advisers were recommending he run a careful campaign, and not rock the boat. They were of the opinion that the more commitments Dewey made as a candidate, the more his hands would be tied as president.”

Dewey, though not a conservative in the Taft mold, ran a far too conservative campaign—more concerned with avoiding error than telling or showing voters what he actually stood for. Dewey’s bland platitudes about “unity” rang vague, hollow, and feeble alongside Truman’s focus on the concerns working voters cared most about: “peace, prices, and places to live.”

The defining moment of Truman’s campaign was a triumph of research-driven demographic analysis, Baime contends. In a speech in Dexter, Iowa, Truman described with outrage how the Republican congress had recently rewritten an obscure law that provided farmers enjoying a good harvest with a way to store their excess grain, rather than hastily having to sell it off at a substantial loss. Truman revealed this secret in Dexter a few weeks ahead of its actual impact, but his speech soon took on the air of prophecy, successfully identifying congressional Republicans with predatory big grain traders. “Within weeks, during the harvest,” Baime writes, “the prescience of Truman’s speech would become brutally obvious to farming communities across the country.”

Baime’s richly textured, fast-moving narrative vividly captures the stories of the race’s potential spoilers, the staunch segregationist Thurmond and the socialist-leaning Wallace. Though Wallace shared much of Truman’s domestic agenda, they diverged dramatically on how to deal with the Soviet Union, and Wallace never entirely trusted Truman’s professed stance on civil rights. As of 1948 he still hadn’t forgiven Truman for replacing him as Roosevelt’s running mate on the 1944 Democratic ticket, thus positioning himself to inherit a presidency Wallace believed should have been his.

One of Dewey Defeats Truman’s most compelling chapters describes Wallace’s courageous campaign tour of the Deep South, during which he refused to speak to segregated audiences or avail himself of whites-only accommodations. Dewey ate and slept in African American homes nearly everywhere he went, and he saw things most of his fellow mid-century white Iowans never knew existed.

Like a lot of vulnerable radicals in the Red Scare years that followed, Wallace would soon abandon many of his campaign’s ideals to support Truman’s war in Korea and align himself with mainstream Cold War liberals. But his run for the presidency nonetheless placed him in a grand tradition of heroic, progressive, outsider presidential campaigns including Eugene V. Debs in 1912, Fighting Bob LaFollette in 1924, Wallace in 1948, Shirley Chisholm in 1972, Jesse Jackson in 1988, and Bernie Sanders in 2016.

While Baime hints at some notable parallels to the 2016 election, for the most part his narrative portrays a time far removed from our own. For one thing, it correctly identifies the internal conflicts within both parties in 1948 as anticipating by several years, but not actually precipitating, the eventual party breakdown and reconfiguration that shifted Southern conservatives and white supremacists to their proper home in the GOP, flipping the Solid South and dismantling Roosevelt’s tenuous New Deal coalition.

Roosevelt and his moderate 1940 presidential opponent Wendell Willkie had similarly recognized the natural schisms within the parties and discussed a plan for hybridization or rational realignment in summer 1944. But with both men dying within the next 10 months, neither had time to do anything to develop or implement their plan.

Moreover, the 1948 election, as no contest since, pitted four men from farming families against one another, and hinged largely on the farm vote. Many Americans, Truman included, adhered to the “farm fundamentalist” economic theory that as go farmers, so goes America. Of the four, only Truman’s background hewed close to the small-farmer constituency that ultimately swung the election in his favor, as his remarkable empathy for and ability to speak to their concerns carried the day.

Truman adopted his scorched-earth rhetoric (a strategy Dewey himself had deployed unsuccessfully against Roosevelt in 1944) as a calculated risk. As Irwin Ross writes in The Loneliest Campaign: The Truman Victory of 1948, Truman’s campaign team “had shaped a strategy in which rhetoric was going to play the key role. The art of politics was practiced not to achieve compromise, but to achieve victory.”

Ironically, the more Truman brought his “Give ’em hell!” assault on the “do-nothing” 80th Congress to voters—no matter how massive and enthusiastic the crowds—the more the media and political elites insisted that he was a man far outclassed with no chance to win. (In the next decade, those same elites denigrate Eisenhower’s mass appeal as well.) Pundits accused Truman of vulgarity and of desperately resorting to low blows and cheap shots to boost his sagging campaign, while at the same time praising Dewey for staying above the fray. As Pietrusza writes, “Truman’s trip had been undignified, unprecedented, and unpresidential.”

Baime characterizes it differently. Truman’s “language was the language of the common man, stripped bare of ‘two-dollar words,’ in Truman’s parlance,” Baime writes. “He was out to protect the hundreds of millions of Americans powerless against the forces of greed that unrestricted capitalism could sometimes foster, to keep power in America where he believed it belonged: in the hands of the people. In doing so he was becoming more than a political candidate. He was becoming an American folk hero, and he was incessantly warning voters that the stakes of a presidential election had never been higher.”