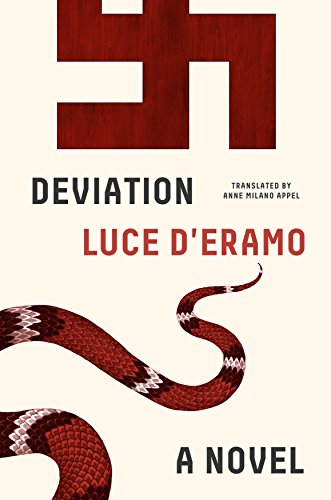

Deviation: A Novel

Deviation is an amazing, courageous book by an amazing, courageous woman. It is not, however, the eye-opening book a reader might expect.

The promotional material explains that author Luce D’Eramo “was a devoted teenage fascist in the waning years of WWII” who “decided with a stunning mixture of bravery and foolishness to leave [her Italian] home and volunteer at a German work camp. She was hoping to discredit the rumors she had been hearing” about Nazi atrocities.

For most of the period from February until October 1944, D’Eramo worked at slave-labor factories at Siemens, I. G. Farben, and Dachau, until escaping from the last camp during an air raid. Four months later, when a building collapsed on her in Mainz, Germany, she was permanently paralyzed from the waist down.

This autobiographical novel was written over a period of 30 years, published in Italian in 1979, and just now translated into English. The author died in 2001.

With stunning detail and honesty, D’Eramo explores her physical pain, the unreliability of her memories, daily life in the labor camps, and the depths of inhumanity she encountered.

When she was first injured, for instance, she liked “to clench my teeth and tighten my fists, so tense that I shook, spasmodically, mentally willing my legs to move . . . I dreamed that I was running. I would wake up panting, and each time I had the sensation of having arrived a fraction of a tenth of a second too soon.”

However, the book brushes past the most important and unusual part of D’Eramo’s story: her original fascination with fascism. The only attempt at an explanation is the following, terse exchange with a French bunkmate at Farben (where D’Eramo calls herself Lucia):

“Martine wanted to know what the Italian girl had ever found good about Fascism.

“As she listed the merits of her country, its dedication to the cause, its fortitude and courage in difficult times, Lucia felt a sense of vagueness that humiliated her and for which she held Martine responsible.”

Without a more complete picture of D’Eramo’s upbringing—without any before-after comparisons of her political views—her descriptions of the labor camps, horrifyingly pungent as they are, become just another on the “Holocaust” bookshelf.

Nor does D’Eramo give more than a couple of flicks toward the core of the Holocaust, the Nazis’ genocide against the Jews.

On its own terms, however, Deviation is a compelling book, written with a powerful immediacy.

From the opening line—“Escaping was extraordinarily simple”—the novel jumps straight into D’Eramo’s flight from Dachau, without any explanation of who she is or why she is in that notorious place. (Contrary to common misunderstanding, Dachau was not an extermination camp dedicated to Jews. Rather, it was a slave-labor facility for political prisoners, religious minorities, prisoners of war, and other “asocials.”)

The first half of the book covers the author’s nomadic efforts to survive during the war’s last, freezing winter and her paralysis. Then, doubling back, D’Eramo describes her naïve and relatively less grueling months at Siemens and Farben. Finally, in one more re-doubling, she tries to dig up the memories she has repressed over the decades and analyze why she has trouble remembering.

“I had based the recovery of my memories on a falsehood; therefore that recovery was also unsubstantiated,” she decides at one point.

She also ponders how people—including her fellow prisoners—can lose their basic humanity. “Hatred of the Nazis became an exclusive passion that did not socially unite the inmates,” she realizes. Not only were the inmates divided against each other by the Nazis’ carefully color-coded badges marking Jews, political prisoners, homosexuals, Roma, and other categories, but “along with his physical existence, each one fought tooth and nail to defend his personal identity.”

While D’Eramo never talks much about her political change of heart, she reveals some other motivations for her actions.

She obviously felt a need to punish herself for her class privilege. After she is taunted by fellow prisoners at Siemens for the preferential treatment she is accorded, as a fascist volunteer from Italy, she decides to eat with the Russians and Poles—who, under the Nazis’ strict ethnic hierarchy, were treated worse than D’Eramo’s Western bunkmates. However, she won’t go so far as to join the Eastern Europeans in their more wretched dormitory.

Another, albeit unacknowledged, motivation seems to be standard teenage rebellion. She frets at the prospect of a curfew, “home at sunset, my mother’s eyes aimed at the grandfather clock in the hallway if I was late coming back . . . not being able to go out anymore except accompanied by my mother, to those unbearable ladies’ teas like in Rome.” Hell no, Dachau has to be better than that!

D’Eramo—whose essays and other fiction were praised by such literary giants as Alberto Moravia and Ignazio Silone—does not make it easy for her readers. In addition to the time shifts, she also switches the narrative from first to third person and alternates her name among various versions of Lucia.

Although this is not the fully realized book it could have been, Deviation is well worth reading and an important addition to the Holocaust library.