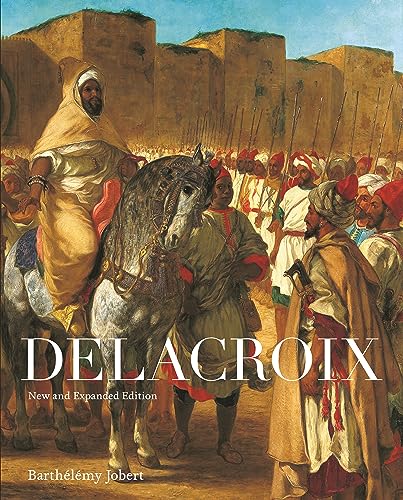

Delacroix: New and Expanded Edition

In 1997 Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) scholar Barthélémy Jobert published a monograph to honor the 200th birthday of this perplexing 19th century painter. In 2018, Jobert revisits his first edition to freshen it up in honor of its 20-year anniversary.

Twenty years may not seem very long when relating to centuries and the question is, has anything been discovered about Delacroix during that brief span that hadn’t already been noted in the previous 200 years? Well, not necessarily. Most museum Delacroix collections have remained stagnant and exhibitions have relied on tried and true showings. What has evolved is the knowledge surrounding the context and intensity in which Delacroix lived and worked.

Continued study on Delacroix’s contemporaries, his rivals, and his artistic and literary influences, has increased the collective body of knowledge in the field of Art History. Retrospectives and publications around names such as Jacques-Louis David, Théodore Géricault, Antoine-Jean Gros, Baron Gérard, Anne-Louis Girodet, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Raphael, Rubens, Veronese, Tintoretto, Goethe, Byron, etc., have indeed expanded the realm in which Delacroix can be examined.

Updates in technology have made archived documents much more accessible via online sites. Cameras are able to make public 3D images of works previously reserved only for private installations. Meticulous restoration techniques have allowed for a handful of Delacroix’s works to be renovated. These processes result in completely new perspectives, which in turn results in a completely new way of seeing Delacroix. Jobert seizes this opportunity.

While identifying Delacroix as a history painter, a literary painter, a Romanticist, Realist or Orientalist, may satisfy basic art history categorization, what Jobert is after is completely different. He is not interested in a study of one painting or another, per se. Nor is he focused on a particular theme, genre, relationship or time frame.

Jobert is looking to reach the heart of Delacroix’s artistic “creative process.” He has rearranged this book to satisfy that intent. Delacroix may have changed tactics as he matured, but a certain personal dedication, enthusiasm, perspective, and tenacity remained constant. Chapter by chapter Jobert articulates Delacroix’s various “complexities,” “contradictions,” “ambiguities,” and “weaknesses” even in the midst of a successful artistic career.

Proceeding chronologically, keeping his examples contained, Jobert examines seven blocks of works in light of the particulars of Delacroix’s artistry starting with a brief biographical sketch of his youth, close friends and family. This first insight into his creative personality is gleaned from quotes from his journals, comments connecting drawing with literature and music, and formulation of a personal art theory

One section focuses on Delacroix’s Salon paintings between 1822–1827. This was the start of his public life as well as the start of the grim reality of the brutality of art critics. The battle of the established Neoclassical school dominated by Ingres verses the “avant-garde” of Romanticism roared vicious and deafening. The drama rings with a soap opera flair. It is hardly possible that Delacroix’s love-hate relationship with the Salon is a true one. As controversial as his approach was, Delacroix still sold his paintings and won commissions.

A major treat is nestled in the section on the Morocco drawings, which is the only one focused on Delacroix’s unfinished sketches. This chapter could itself be flushed out further into an entire book-length study. Jobert covers his bases, though, and delivers a solid, thoughtful discussion. The artwork is excellent and serves well as samples of the complete journals Delacroix kept. This point in Delacroix’s life serves as a marker of change in his productive life.

Upon returning from that pivotal Morocco trip, Delacroix worked with an almost Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder fervor, accepting huge commissions, painting for the Salon, drawing for his personal interests, keeping a journal, running a studio, and dealing with fragile health concerns. He even found time to reconsider favorite themes.

Jobert, in the final chapter, sets some of these themes side by side for comparison. Animal motifs are continued when A Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother (1830) comes around again in Lion Mauling a Dead Arab (1847). Older paintings are made new with examples such as: The Abduction of Rebecca in 1946 and again in 1858; Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women in 1836 and 1858; or the Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople from 1840 (a Salon entry) and also 1952 in smaller scale.

As if this quantity of production weren’t enough, Jabot concludes with the posthumous discovery of boxes upon boxes of 6,000 Delacroix drawings. There is, ultimately, ample evidence supporting the comment Jobert makes in his introduction: that with Delacroix, “a fundamental element stands out: an iron will in the service of tremendous creative power that places him among the very best.” And that is a unique creative intensity entirely worth revisiting with this latest Delacroix: New and Expanded Edition.