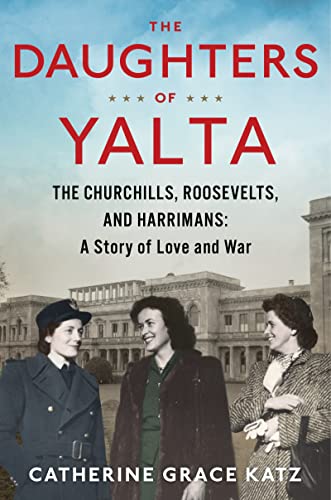

The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War

What if Jane Austen could write meticulous diplomatic history combined with a social portrait of American and British aristocracy? The product might resemble The Daughters of Yalta by Catherine Grace Katz.

Two of the Big Three at the Yalta Conference in February 1945 brought their daughters, Anna Roosevelt and Sarah Churchill with them to Crimea, as did the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, W. Averell Harriman, whose daughter Kathleen was a war correspondent working out of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. The third of the Big Three, Joseph Stalin, had a daughter who later became well known as a defector, Svetlana, then aged 19, but she did not attend. Anna, Sarah, and Kathleen (ages 38, 30, and 28) assisted their fathers and steadied them as they tried to plan the future of post-war humanity.

Harriman’s daughter Kathleen was the most adventurous of the three. Her father, the fourth richest man in America, owned the Union Pacific Railroad and had visited Russia in 1899 on the Alaska Expedition ship hired by his father. An avid sportsman, Harriman founded the Sun Valley ski resort in Idaho, and let Kathleen manage it while he was away. She became a champion skier as well as an equestrienne and hunter.

A public servant politician as well as a businessman, W. Averell Harriman was sent to Moscow by Roosevelt in 1943. He arranged for Kathleen to come with him. She won Averell’s favor in part by helping him break off his awkward affair with 20-year-old Pamela Churchill in London, unhappily married to Winston’s son Randolph. After each of them had other affairs or marriages, a 51-year old Pamela married the 79-year-old Averell Harriman in 1971. (When he and I overlapped at the Wilson Center in Washington in 1977, I noticed that he turned off his hearing aid when bored by conversations, but that he regarded it as very important to inform Congress on how he saw U.S.-Soviet relations.)

After Averell’s death in 1986, President Bill Clinton sent Pamela to Paris as U.S. ambassador, where she burned through tens of Harriman’s millions to the discomfiture of his offspring including Kathleen, who sued her one-time roommate in London. This is the kind of social history that Katz details as the context for the Yalta negotiations and the subsequent lives of the three daughters and their fathers.

Anna Roosevelt also ran interference for her father as he tried to shield from the long-suffering Eleanor the visits of his long-time paramour, Lucy Mercer. At age 38 in 1945, Anna was the oldest of the three Yalta daughters. She was happy finally to have received her father’s confidence. She was one of the few persons with whom he could relax.

Sarah Churchill flew in Great Britain’s Women’s Auxiliary Air Force but happily joined her father for the Yalta trek, which he feared might make him sick again, as happened after the Tehran Conference in 1943. Sarah was having an affair with John Winant, the U.S. ambassador to London, that ended badly, perhaps contributing to his suicide in 1947. She became an actress and performed in California in films, television, and shows with Jack Benny. She died in 1982 at 67.

When Averell’s Kathleen died in 2011 at age 93, Margalit Fox wrote in The New York Times that her “life is a window onto both Gilded Age America and the changing role of American women in the era between the world wars.”

Not unlike the novels of Jane Austen, Katz casts a spell as she relates the twists and turns in the lives of her main characters. But her account of the Yalta Conference is as informative as it is intriguing. She relates, for example, how Roosevelt dispatched Harriman late at night to the Vorontov Palace where Churchill stayed to show him a draft letter to Stalin trying to bridge their divergent priorities with respect to Poland. When Harriman returned to the Livadia Palace, where Roosevelt resided, with a few suggestions by Churchill, FDR then gave the revised letter to Harriman who took it to the Koreiz Villa where Stalin slept.

Each of the pages in which Katz describes the Polish issue are based on quotes from four or five archives, which she has strung together to provide a unified tale.

The entire book by Katz is informed by research in dozens of private and government archives and documentary collections in the United States and United Kingdom. Katz does not cite any Soviet sources. They would not be central to her story, but it would be interesting to know how Stalin and his entourage perceived the three sisters, one of whom—Kathleen—was said to be the best-known American woman in Russia after Eleanor Roosevelt and Deanna Durbin. The Soviet diplomat Andrei Gromyko wrote in his memoirs that after he and Stalin visited an ailing FDR in the Livadia Palace (once the abode of Tsar Nicholas II), Stalin asked “Why does Nature [God?] make him suffer so?” Just two months later, Roosevelt died.

The Daughters of Yalta adds a human touch to the excellent but more conventional diplomatic histories by Diana Preston, Serhii Plokhii, Fraser Harbutt, and Diane Shaver Clemens. The Clemens book (Yalta, 1971) offers a broad theory Katz does not address. Her reading of the documents suggested that FDR and Churchill were willing to make concessions on Poland to Stalin if he agreed to their priorities—a strong United Nations and a major role for France in postwar arrangements. Instead of a sell-out of Eastern Europe, she pictured a reasonable compromise between governments pursuing their basic goals—in a situation where the Red Army sweep toward Berlin was a fact of life.

Another broad interpretation is that of Nigel Hamilton in his War and Peace: FDR’s Final Odyssey, D-Day to Yalta, 1942–1945, also published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, in 2019. Hamilton portrays Churchill as an inspiring orator but an impetuous military dunderhead. Roosevelt, despite his failing health, provided the long-term perspective and steady hand that climaxed in the decisive D-Day invasion.