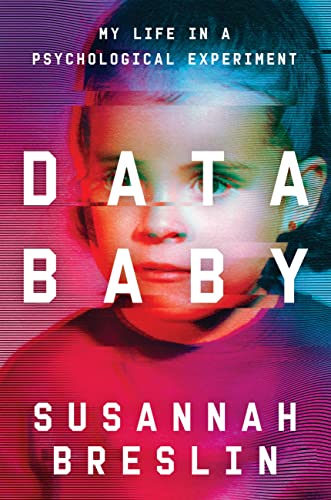

Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment

Susannah Breslin is an accomplished journalist. She writes about sex and pornography. She produces documentaries and television series.

Her stated goal in writing Data Baby is to explore the link between her being in a 30-year psychological research study as a child and young adult and who she turned out to be in adulthood. Breslin’s book is a quest to find and understand herself.

The author queries how being psychologically tested and scrutinized periodically in childhood affected her sense of self and choices she made in her life. Did being in the study alter her life trajectory? Did the investigators know her better than she knew herself?

The writing is in journalistic style with short, active voice sentences. This makes the book very readable.

The shortcomings of Data Baby are several. For one, Breslin’s questions are not answered. The study data were lost to her. The premise of the book is flawed and shows little psychological sophistication or know-how about child and adult psychological development. Children are shaped psychologically and emotionally by their early life experiences with people they most spend time with, usually parents.

In Data Baby Breslin reveals some information about her early life with her parents and her recollections of what each was like and their interactions with her. This early time in her life points the way to what kind of person she turned out to be. Her being in the psychological study does not.

The book reads as part autobiography, part memoir. It is a regurgitation of events and feelings, but without a grasp of how to pull her life story together. Data Baby is not a psychological inquiry, as she had hoped it to be. With these constraints, the story is tiresome with not much compelling about her event-laden story.

The reader wants to know what she discovered about herself. How did she learn it? Did she make changes in her life based on what she discovered? What were the changes? How did they turn out? The details of her early life at home do reveal some clues about who she will grow up to be. But Breslin neither focuses on these clues nor makes conclusions from them.

Data Baby is not an enjoyable or informative book for readers. The story meanders. Its path is unclear. The author’s tale does not answer her original question of why she turned out to be who she is. A preliminary consult with a psychiatrist or psychologist might have helped Breslin decide if her goals in writing the book were attainable or flawed.

Everyone’s life is its own psychological experiment, regardless of being in a formal study or not. The missing meat in this book is the study of Breslin’s own psychological experiment in living and, more importantly, in understanding her life.