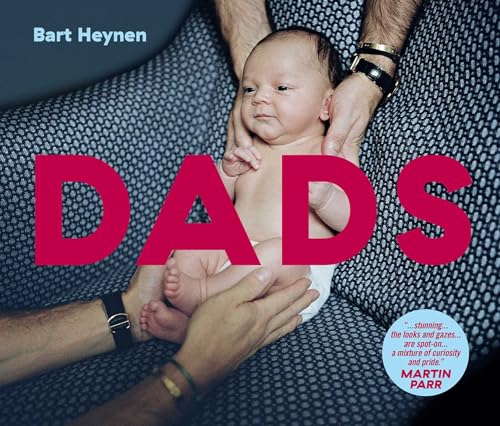

Dads

This gorgeously produced book is a baby photo album with one major difference. All the Dads are gay men, married or single, who have become parents through surrogacy or by adoption. The more than 40 families include a range of ethnicity, age, occupation, and location, and have very different stories to tell about the ways that they became fathers.

Bart Heynen, a photographer and gay father living in New York City, found it easy to connect with and photograph “gay dads and their families in the city.” His approach quickly evolved from a portrait or Instagram approach to one where he managed to capture the dads and their children casually off-guard. Only a few of his subjects were too guarded to respond to this informality as is evident in the pictures, though all of the visuals are beautiful.

One standout among the relatively posed is “Pedro single dad of triplets with Mandi (surrogate) and Sloane (egg donor). This is followed on the next page by a more relaxed look at Pedro and his three children enjoying a weekend breakfast with the donor and the surrogate (inscribed on their T-shirts) while he explains to the triplets, who seem to be amazed and amused, how they were conceived.

Heynen’s coverage expanded beyond New York City because of “surprisingly enough, the lack of Black families.” Eventually he captured moments from the lives of Dads and their children in Washington, Miami, Salt Lake City, Omaha, and elsewhere. Inserted casually at is a photograph of Heynen and his partner Rob “with Ethan and Noah at 6.30 a.m.” in Antwerp, Belgium.

Same- sex parenting experienced a boom in the US after same -sex marriage became legal in 2015, although as Heynen reminds us there are still 70 UN Member States who criminalize consensual same-sex acts some with the death penalty.

One of the many interesting things noted by Heynen is the fact that without traditional gender roles to fall back on the division of labor in most homes he visited was very fluid “Ironically, in these families equality has been accomplished organically, while on a national level the ‘Equality Act’ has yet to pass the Senate.”

Many couples involved a range of their gay friends as well as their birth families, some of whom were also surrogates and donors, in the parenting process. Heynen sees it as a plus that currently “two people in a gay relationship cannot have children who manifest both of their genetic contribution,” in that same-sex couples are therefore obliged to adopt a more inclusive parenting model rather than trying to replicate the format of a heterosexual couple.

The book is organized into two main sections; Heynen’s photographs in the first section with a small explanation. In the second half of the book there are a number of essays written by Dads or their children, with an introduction by Heynen himself. While this is probably the most impactful way to organize this material a small gripe is that it would be good in the essays at least to discretely reference the photographs.

This is a brilliant and moving book which illustrates perfectly a quotation cited by Heynen, “‘Love, commitment, and family are not heterosexual experiences, not heterosexual words, they are human words and belong to all people.’” (Harvey Fierstein). Can we expect a forthcoming publication on Moms?