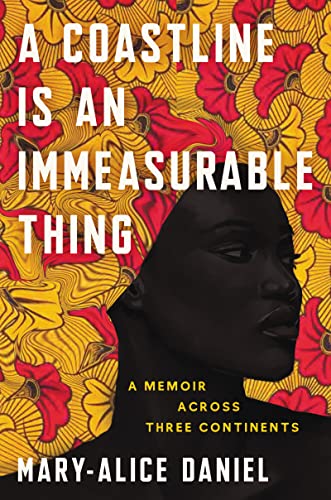

A Coastline Is an Immeasurable Thing: A Memoir Across Three Continents

“Mary-Alice Daniel is an exquisitely elegant young writer.”

Mary-Alice Daniel’s wondrous new work A Coastline Is an Immeasurable Thing: A Memoir Across Three Continents isn’t typical of most memoirs that seek a solid reckoning of sorts. Author Mary-Alice Daniel remains mired in uncertainties. Perhaps this is because she is only 34 and seems by disposition timid and nonconfrontational. It is clear, however, that her fraught relationship with her authoritarian mother dominates her thinking, and she is hesitant to attack her outright.

Daniel tries her best to understand the psychologic havoc inflicted on all of them after her family was forced to leave Nigeria when she was just a little girl. They wound up in England where they lived for several years until moving to America where they lived in Nashville, Maryland, Brooklyn, Detroit, and many other places. She herself is shocked when she realizes her upbringing has been a “concoction of three religions, four languages, and thirty-two addresses across three continents . . .”

It is clear Daniel loves her family but has made great efforts to live her own life. Her path as a writer and poet has greatened the space between them, and she lives in Los Angeles, which she swears has become a promised land of sorts for her. It is where she received her Ph.D. in Creative Writing and Literature from the University of Southern California. Her parents and siblings live on the East Coast. Her memoir is a poetic rendering of a woman in search of herself.

Daniel admits she often feels unmoored. She writes candidly: “But I often remain shiftless. I meander and move for work, school, love. I inherited a spirit of such extreme exophoria—the uncontrollable tendency of eyes to gaze outward. My ancestors were traders and herdsman who roamed the Sahara in search of water. My immediate family and I are transcontinental nomads, relentless in pursuit of something less material. Only five of us migrated to this part of the world.”

Daniel recalls how her father did not want to leave Nigeria until he had to. The situation was deteriorating fast and would only get worse. The family left in 1988. Her parents secured visas to England where her father studied pharmacology and her mother studied zoology. Daniel was raised Christian in a mostly Muslim stronghold of northern Nigeria because her grandfather brazenly converted to Christianity; he was the first in their village to do so.

Daniel recalls how lonely it was for her in England since her parents were almost never at home; they were always working or studying. She writes movingly: “I am retroactively aware of how my young parents must have suffered. I pity my parents in the past tense. They did not know the wreckage we would wade through as lonely immigrants in lonely lands.” But she doesn’t really sound sorry for them. She sounds angry at them for all the repeated desertions and the sting of that is too painful for her to address head-on. We can sense she feels insufficiently loved. In one of her moving poems, “Somewhere along the Base of the Uncanny Valley,” she seems to circle around this. She writes: “I am an apprentice of this pointless supposition/Sometimes I can tell, by a girl’s name/ How or how much her parents loved her . . .”

The language of her childhood home was Hausa. She recalls being forced to attend church every Sunday and say her prayers aloud with her siblings each night. She found it distasteful and never sensed the presence of God, only of being coerced. It disturbed her how much her mother was concerned with how things appeared to others. She took all the children to have their clothes specially made for them by a seamstress in London. When her mother left the family home in England for a year to pursue a postdoctoral certificate in education, Daniel was inconsolable. Even though her mother annoyed her, her intense attachment to her mother was undeniable. She felt overwhelmed by all the flux, leaving her with a “floundering cultural identity, a feeling of not having a home-or of having one and being lost to it.”

When Daniel attempts to describe Nigeria, there is a romanticism linked to her descriptions. She seems almost to hide beneath Nigeria’s vastness as if it could magically absorb some of her pain. The country has over 500 languages and large tribes dominate the political culture. It is today a nominal democracy with plenty of sectarian strife.

But her memories are really inherited ones from her mother because Daniel left at such a young age. She barely has any direct recall to the place. When she returned with her family for a visit, she was disturbed by the Nigerian style of speaking which seems to dwell upon continually teasing one another about silly things. She found the endless customs tedious, and the submissive gestures expected of the women atrocious. She became exhausted by the constant visiting of distant relatives and the ceremonial gift-giving that took place. Yet one memorable night in Nigeria when she was only seven, she watched her parents dancing on stage “to music they knew and everyone else knew but I did not know. I coveted the feeling of belonging you find in knowing the songs of a place. I became an anomaly. And I felt trapped in a moment, together, too long. The air too close. I was trespassing inside the storybook where I once did not exist.” Without directly saying so, we feel Daniel’s sense of being insulted without fully knowing why. But it is obvious she soon realizes she envied her parents for having had a life in one place for so long their connection to it was undeniable and precious.

Daniel tells us her mother is Fulani, a small Nigerian tribe. They are predominantly cattlemen. Her father is from the Longuda tribe. About her father, Daniel says little. He seems not to have a significant place in her rememberings. She says only that she isn’t close with him. Her mother would preach to her the Fulani values such as grace, moderation, hospitality, courage, and a strong work ethic. But her mother was unavailable to her for the kinds of conversations she wanted to have. When she would tell her mother about a disturbing dream, or problem at school, her mother would robotically reply “Care only when God thinks of you.”

Daniel is a keen observer. She sees how ambitious her mother was, and is, and sees the same striving in herself. But Daniel’s modern outlook on herself is unacceptable to her mother, who still relies on superstitious thinking to make many decisions. Yet Daniel can’t quite break free, confessing her mother “is the love of my life and the main force within it, always pushing me towards or away from something. Towards medical school; away from moving out of state; toward her Nigerian friend’s sons; away from poetry.” Daniel acknowledges their attachment has ferocious undertones, each trying to bend the will of the other.

One can’t help but by overwhelmed by the exquisiteness of her prose, which we sense has been pulled from the deepest regions of her heart. Daniel never tells us about her current life in California. She mentions nothing about friends or lovers or colleagues. Although we sense a burgeoning feminist sensibility, there is a part of her that remains determinably old-fashioned. Someone who still values the restraint her mother taught her about. And perhaps this is the reason she holds back on some things we sense she wishes she could say. She leaves questions swirling around mid-air almost as if she believes answering them might risk massacring something sacred. So she keeps herself in check, revealing much, but holding back when she senses she might cause real harm. And it is this insistence on keeping herself in check that pulls us more closely to her. Mary-Alice Daniel is an exquisitely elegant young writer.