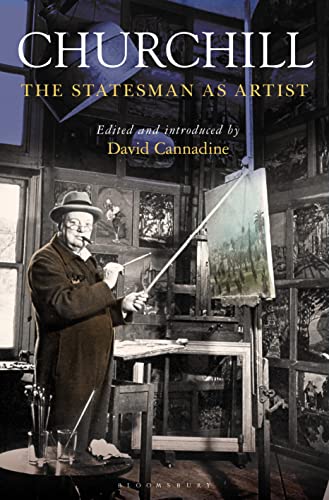

Churchill: The Statesman as Artist

“Churchill: The Statesman as Artist is a comprehensive assembly of Churchill’s contributions as an artist as critical to, yet distinct from, his legendary role as statesman.”

With the release of films such as Dunkirk and Darkest Hour (both in 2017), Winston Churchill (1874–1965) as a famous statesman has recently received much recognition. Post-war generations get a refresher course to world history via these types of dramas. But the renditions do not tell the complete story of the person who was Churchill. For some reason, Churchill, at least in the United States, is destined to be associated in posterity with war, and not so much, if at all, with the Royal Academy of Arts.

Perhaps it is not good drama for Hollywood, but Churchill’s connection to art, painting, and the Royal Academy is nevertheless loaded with riveting political as well as personal insights. Cannadine even presents an argument suggesting that it was Churchill’s artistic sensibilities that were applied to his speeches, conversations, and writings, and are the source of his masterful command of the English language.

Churchill, “delighted in strong nouns, vivid adjectives, rich imagery, polished antitheses, glowing phrases . . .” Both his speeches and his artwork, “were often bright, warm, vivid, highly-colored and illuminated creations, full of arresting contrasts between the light and the dark . . .” Churchill himself described the ideal painting as “a long, sustained, interlocking argument.” Visual imagery was in every sense on par with, or even surpassed, verbal oration.

Based on the framework of this close connection between art and politics, Cannadine integrates primary materials surrounding Churchill’s passion for painting. In addition to Cannadine’s extended introduction, the book is segmented in two parts. The first section reprints twelve speeches Churchill gave in reference to art or in art venues between 1912 and 1954.

Over the decades it is interesting to see just how much more entrenched Churchill became in his convictions regarding the arts. The Royal Academy speech titles themselves go from “The Naval Greatness of Britain” (1912) to ”We Ought Indeed to Cherish the Arts”(1938), to “A New Elevation of the Mind” (1954). It is the arts, Churchill claimed in this later essay, that have a “noble and vital part to play” in the elevation and enrichment of the human mind which will lead directly to the “outlawry of war.” Tall rhetoric for the power of art!

Among these speeches is a complete reproduction of the mini-book Painting as a Pastime, in which Churchill presented a persuasive essay on the benefits of painting above other hobbies. Many a fellow statesman was inspired to follow suit after reading this piece and it is still one of the most convincing endorsements for the continued support of the arts in society.

The second half of the book contains commentary and critique about Churchill’s art with articles spanning 1950 to 1970. Included here are pieces by artist/art critic Eric Newton, art historian/curator Thomas Bodkin, the then director of the Tate Gallery, John Rothenstein, and post-impressionist artist Augustus John. The angle in the second part, therefore, rotates from Churchill’s opinion of art, its importance, and its necessity within an advanced democratic civilization, to a 180 degree about face evaluation and critique of the art created by Churchill himself.

Political acuity was the objective of Churchill’s professional orations, but mental rehabilitation and reverie was the objective of his personal creative endeavors. Admittedly, he could not have done the politics without spending time in the arts. Churchill: The Statesman as Artist is a comprehensive assembly of Churchill’s contributions as an artist as critical to, yet distinct from, his legendary role as statesman.