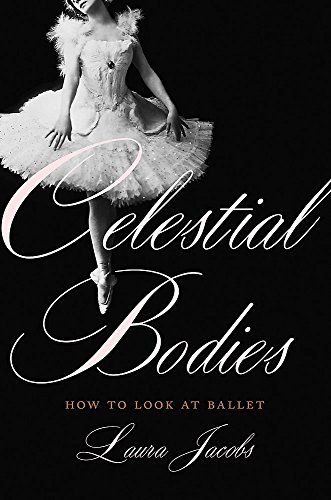

Celestial Bodies: How to Look at Ballet

Laura Jacobs’ Celestial Bodies: How to Look at Dance delves into the lasting appeal of classical ballets like Giselle, La Sylphide, Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and, of course, The Nutcracker. It is part ballet primer and a lively insider peek into the technical aspects and the enduring magic of the dance world.

Jacobs makes the great point that classical techniques taught in ballet schools and conservatoires maintain artistic standards that are constantly evolved and refined through new generations of dancers. Most major ballet companies mix contemporary repertory, but on any given year, rely on the enduring appeal of the classical ballets to pay their bills.

Jacobs brings us into the creative, even poetic, realms of the dance and also, in concrete terms examines the origins and mechanics of ballet from its history in the court of Louis XIV, to the development of the pointe shoe and its transformational powers as the “wings” of a ballerina. The pointe shoe that was the tool that changed the art form. Women previously danced in raised heels, which prevented any possibility of ballone or the vocabulary of what would be balletic artistry for the ballerina.

Jacobs deftly analyzes George Balanchine’s Serenade, the first ballet he made as a Russian émigré choreographer in America who would define the American postmodern aesthetic, while preserving Russian classicist vocabulary.

Her examination has typical Balanchine subtext, but Jacobs quotes Balanchine that in his instruction that ballet simply “means what you see.” And Jacobs elaborates that point to encourage us to let our imagination dance along with the artists. Not to be caught up in any literal meaning, even when it is a story ballet or even when there is an expressed intent of the choreographer, but to view dance as bodies moving in space.

And, of course, everyone understands what they are seeing when Anna Pavlova, Maria Tallchief, Margot Fonteyn, Gesley Kirkland, and Susanne Farrell, among other prima ballerinas, are dancing these classical roles, as Jacobs articulates what they bring specifically to them. Jacobs weighs in on male stars including Vaslav Nijinsky, Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and current stars Angel Corella, David Hallberg, and Ethan Stiefel.

Meanwhile, there is the music of ballet. Her chapter on Tchaikovsky is an exploration in the music-choreographic interplay through his collaborations with master choreographers Marius Petipa/Lev Ivanov—Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and The Nutcracker.

Jacobs’ finale is her eloquent bow to the achievement of the courage, conviction, and individual artistry of the ballerina who embodies ballet history and puts her imprimatur on it. If “ballet is woman,” as Balanchine was quoted as saying, she writes of the powerful subtext of a woman on pointe, articulating in dance the creative mind of a classical choreographer.

Even though the book focuses on ballet classicism and history, Jacobs’ incisive commentary on neoclassic and contemporary dance is equally instructive; consider Nijinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, that seismic leap into modernist movement. Jacobs touches on other visionaries 20th century dance including Martha Graham, Agnes De Mille, and Isadora Duncan. The world’s premiere dance companies required dancers to be much more versatile in postmodern genres on top of being superb classical technicians. They are also required to be at their physical peak to meet the demands of a generation of innovative choreographers.

That is Jacobs’ core thesis about how audience members should approach it. But on equal ground is her dissection and examination about choreographic intent, the interpretive artistry of a dancer, and the cultural significance of the most revered and enduring ballets in the world.

As accessible as Jacobs makes this history for general readership, Celestial Bodies is basically for students of dance and avid balletomanes. Jacobs is a Vanity Fair staff writer, editor in chief of Playbill, novelist, and longtime arts journalist.