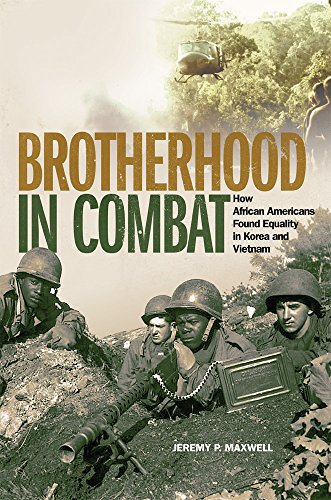

Brotherhood in Combat: How African Americans Found Equality in Korea and Vietnam

The service of African-Americans in the armed forces of the United States should be well realized by everyone by now. From the Revolutionary War to the present, they have sacrificed for their country in spite of being denied those rights for much of that period which the rest of our citizenry has taken for granted. Their primary reason for serving has been the idea that military service would be the quickest way to prove themselves worthy of all the benefits of citizenship.

However, and unfortunately, this has not turned out to be the case, and it has been a long row to hoe. Long considered as unreliable or untrustworthy, they were relegated to menial labor and support work, digging latrines, building barracks, roads, and the like. When employed in combat, they were just as likely to be blamed for failure by their white officers and higher chain of command or to go unrecognized for any success.

Adding insult to injury, they were many times inferiorly housed (segregated), fed and paid at a lower rate than their white counterparts, and subject to the racial prejudices of their officers, particularly when it came to promotions, awards, and decorations. They were also last hired when manpower needs dictated and first fired when it came to disbanding their units when their services were no longer required and demobilization was necessary.

Having proved themselves, they believed, from the Civil War through World War II, the equality they sought was not attained. It was only after the latter conflict that progress was made through the lobbying of Eleanor Roosevelt, executive orders by President Harry Truman, and the urging of others that the military, a notoriously conservative establishment, began to provide any measure of equal treatment, especially when budgetary requirements were considered.

Consequently, the integration of the armed services found considerable advancement during the Korean War in spite of ongoing prejudice and racism. Indeed, many white soldiers found that they had no problem serving alongside blacks in the crucible of combat where one expects one’s buddies to have their back and vice versa.

That crucible of combat, where survival is utmost, melded the races to the point where one generally did not notice the skin color of the man next to one and unit cohesion was primary in fighting the enemy. That was progress one could see. However, later in the Vietnam War, there was less of this to be seen once opposition to the draft and wartime manpower needs got in high gear. Problems remained as a result.

By the time of Vietnam though, integration in the military was largely complete. Yet continued social unrest at home and lack of progress on equality there (the height of the Civil Rights movement) led to additional troubles in the ranks in opposition to continued perceived racism, prejudice, and the fact of fighting for a country which still did not provide the same benefits and opportunities to all.

If there is any consolation, most of the problems in Vietnam tended to be in the rear areas and support bases where illicit drugs, alcohol, boredom, and down time virtually encouraged trouble. There were even problems onboard Navy ships in theater, brigs, and stockades where overcrowding and widely varying courts martial and judicial consequences were experienced.

In any event, it was difficult overall for the United States military to make additional progress on equality when there was no such thing at home at the same time that Communist propaganda, in each conflict, was making the same point in an attempt to foment dissension in ranks. Hopefully, we have learned our lesson, and there is a united front in our armed forces.

Although there are no photographs or maps included, there are two tables. One lists statistics on captured personnel in Korea and the other shows the troop buildup in Vietnam over the years. Strangely, neither provides any breakdown in terms of race but were apparently included for general informational purposes for each conflict.

There are traditional footnote citations, and the bibliography shows research in many government archives and publications and primary and secondary sources such as books, theses, dissertations, papers, and articles.

Equality must always be considered a work in progress in this country given its history. However, it is gratifying to see that, finally, at least our military is coming around to the perspective that soldiers should be just that when bullets do not recognize or differentiate skin color.