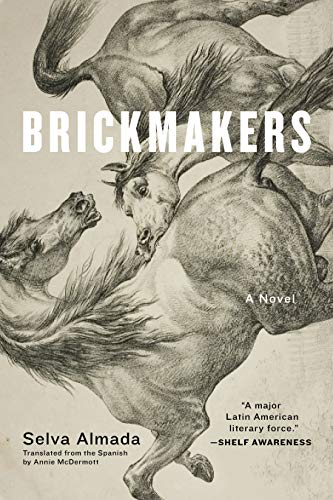

Brickmakers: A Novel

“Selva Almada manages to get inside the minds of her characters.”

In a small town in Argentina, two young men, Pájaro Tamai and Marciano Miranda, lay dying in the mud next to a carnival Ferris wheel. No one seems interested in saving them. Their only companions are memories and fantasies.

Thus begins Selva Almada’s intense, eloquent novel, Brickmakers. The rest of the novel is devoted to showing the reader how and why the two men lose their lives. Yet Brickmakers is not a conventional murder mystery—it is a picture of the destructive power of machismo on the indigenous men and women of this community. Almada’s characters are called “indios” by others in the community, indigenous people trapped in the lowest rung of their society. That, too, is a cause for the men’s rage and brutality which, tragically, is expressed against each other.

Pájaro and Marciano have somehow osmotically absorbed their fathers’ irrational feud. No one seems to know why Oscar Tamai and Elvio Miranda became bitter enemies, but their hostility continued as long as they were part of the community. Long before their sons’ feud reaches its tragic denouement, Miranda was brutally murdered outside a bar and Tamai deserted his wife and family and moved South. Pájaro and Marciano, once childhood friends, seem to have been fated to become enemies. Pájaro seethes with hate for his father who treated him brutally; Marciano is furious at the loss of his father. Those passionate feelings about their fathers fuel their enmity.

The young men’s hatred comes to a boil when Pájaro becomes sexually involved with Marciano’s younger brother Angelito. In a macho society where women exist to satisfy men’s sexual cravings and quietly endure their abuse, and where men’s sense of masculinity is fragile, the ultimate violation of machismo is homosexuality. Angelito, the catalyst for the final tragedy, is always seen through the eyes of other characters. His older brother feels disgust at his open homosexuality and wants to beat him into heterosexuality. Perhaps the most touching portrait is of Pájaro’s confusion at his attraction for Angelito. The violent homophobia he has learned is at odds with the powerful desire he feels. There is, alas, no place for that kind of love in this community.

Almada’s greatest compassion is for Estella and Celina, the wives of Tamai and Miranda. They are survivors who must manage the families’ brickmaking businesses and head their households in a culture that does not respect women as anything but sexual partners. Nor can the wives expect much from their husbands beyond occasional sexual satisfaction. The men may eat and sleep at home, but they spend their nights drinking together in the local bar.

Brickmakers is a vivid group portrait: of the feckless fathers who rebel against the authority of their strong wives; of the sons whose tragedy is to become like their fathers; and of the wives who ultimately have to become the heads of their families and the breadwinners. Using third-person narration, Selva Almada manages to get inside the minds of her characters. While much of the novel is realistic, Almada moves into a more surrealistic realm with the dreams of the dying young men who fantasize conversations with their lost fathers. There are also comic moments that underscore the absurdity of the fathers’ feud.

The small Argentinian town where Brickmakers takes place may seem alien to an urban American reader, but the violent, misogynistic, homophobic masculinist culture Almada depicts can be found all over the world.

Annie McDermott’s new, highly readable translation makes Almada’s superb 2013 novel available for the first time to Anglophone readers. It is bound to make the reader hungry for more of Almada’s award-winning work.