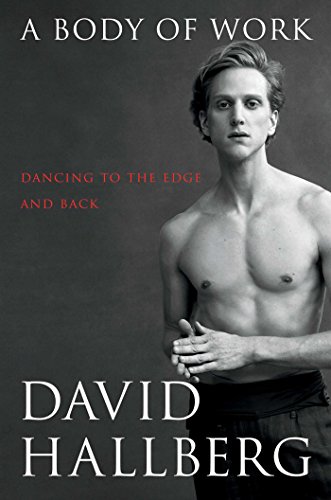

A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back

“[a] well-written memoir.”

In his fascinating but sometime frustrating memoir, A Body of Work, international ballet star David Hallberg recounts his training, his rise to the top of his profession, the serious injury that led to a two-year period of physical and emotional healing, and his battle to make a successful comeback.

As a young boy in Phoenix, Arizona, Hallberg fell in love with dance after watching a Fred Astaire film on television. His loving, supportive parents sent him first to learn tap dancing. When the boy discovered ballet, he found his calling and began training at 13, which is late for a ballet dancer. Dance was young Hallberg’s escape as he suffered taunting and bullying at school for his effeminacy.

After years of training in Arizona, Hallberg spent a year at the Paris Opera Ballet, after which he began his affiliation with the American Ballet Theatre. As he rose to the top at that company, he started making guest appearances all over the world and was the first American to be invited to become a principal dancer with the Bolshoi Ballet.

A serious injury to his foot threatened to end his career. Not being able to dance threw Hallberg into an emotional tailspin. He spent two years in Melbourne, Australia, healing physically and emotionally, and is now back on top at the American Ballet Theatre.

Hallberg’s book is a fascinating self-portrait of a man obsessively dedicated to his career. Like many writers of memoirs, he doesn’t forget those who treated him poorly: the boys and girls who taunted him at school, the fellow students in Paris who snubbed him, and the ballerina who made clear that she didn’t like dancing with him. Hallberg doesn’t forgive or forget. He is equally generous with praise of his teachers and coaches, the ballerinas he particularly liked, particularly Natalia Osipova, and the three Australian therapists who healed him mentally and physically. He barely mentions his male colleagues.

Hallberg is open about his homosexuality but beyond descriptions of his first boyfriend when he was 13, he doesn’t talk about his personal life. He says that being gay was no problem for him in Russia, a brutally homophobic society. Were prestigious artists protected in Putin’s Russia? It would have been nice to know more about this aspect of his experience.

Like many dancer’s memoirs, A Body of Work chronicles the grueling work a dancer endures: the years of training, the strenuous daily classes, the marathon days of rehearsal and performance. The reader senses the hermetic life of a dancer Hallberg seems to live for and through his dancing.

He recounts that in one three-month period he flew more than 45,000 miles, hopping from one guest engagement to another. It is no wonder that he had an emotional meltdown when it looked like he might not dance again. Yet the book doesn’t tell us what Hallberg discovered about himself during his dark night of the soul beyond his ability to dance again.

Is there more to Hallberg’s life than he shares here? His emotional moments—there is a lot of weeping described in the book—are all about himself, not about meaningful connections to other people beyond his parents, brother and the boy he loved as a teenager. Is he close to anyone offstage? Like many self-portraits, we see a man alone in the frame. The photograph of Hallberg having breakfast by himself at the counter of his favorite New York diner underscores the verbal picture we get of this great dancer in his well-written memoir.