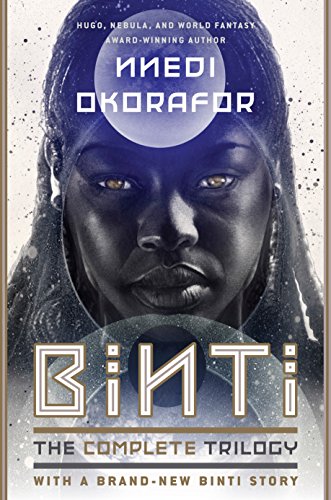

Binti: The Complete Trilogy

“Okorafor’s future world, built out of real cultures and fully realized characters, should establish a new standard for science fiction in the 21st century.”

Nnedi Okorafor is among the finest and most influential science fiction writers working today, and her Binti stories are landmark works of Afrofuturism. The three major works (Binti, Binti: Home, and Binti: The Night Masquerade) are each novellas, published now for the first time as a single book. They and the one new story (Binti: Sacred Fire) together mass only a mid-sized hardcover, albeit one of extraordinary significance.

In Binti, Okorafor imagines a world in which humans have joined a community of space-going, intelligent beings. This is not a future in which humans are culturally dominant; nor is it one in which humans are mono-cultural. Okorafor refutes the space opera trope of a unified (almost universally white) Earth. She presents instead a world in which different groups maintain different traditions, languages, politics, and cultures, and in Binti’s future, humanity is African.

Protagonist Binti is Himba, part of a group that today live in parts of Namibia and Angola. In her future, the Himba are masters of communications technology, producing the finest “astrolabes” available. They also live traditionally, maintaining their practices of faith, family, and food. The Himba are patriarchal, and though women are wise users of technology, a girl’s destiny is to marry and have children. Women do not leave the community. No Himba does.

Binti, like all Himba women, wears otjize, the distinctive ochre paste that protects and marks the skin. Her hair is woven into mathematical braids. She dresses in a stiff upper wrap and long skirt. She is both a woman of the future and an African woman. She carries herself out of her home community in the first pages of the book, and into space, travelling to Oomza Uni, the galactic university where she can study mathematics as no member of her community ever has before.

Binti struggles not only with the loss of her community, but also from her identity. The Himba are subject to the Khoush, another African group that comprises the majority of human space travelers. The Khoush treat the Himba with contempt. More urgently, they are also at war with the jellyfish race Medusae, who attack Binti’s ship en route to Oomza and kill all aboard but her.

Okorafor uses mathematics as a symbol of harmony. Binti is a Master Harmonizer, one who can create equations and social unity with equal facility. Creating peace in the midst of death becomes her role. The galaxy, like Earth, is not accustomed to peace, and constant misunderstandings and provocations ensure that violence is as prevalent as harmony and knowledge.

The Binti stories explore Binti’s struggles to harmonize in space, at Oomza, and on Earth. Of those settings, Okorafor’s evocation of the Namib desert and its people is by far the most engaging. Here are multiple cultures, both ancient and sophisticated, living uneasily in the desert landscape. Tradition maintains a kind of stability, but it fails to prevent cultural clashes. Gender roles aspire to create spaces for everyone but restrict innovation and ambition.

The Binti stories’ resistance of utopia is their great strength. The future can be beautiful and interesting, yet still chaotic and imperfect. Gender remains a stumbling-block even in a universe where many beings have no gender at all, because the presence of other ways of being doesn’t negate centuries-old cultural practices, which themselves have value that offsets the obstacles they raise.

If the Oomza-set sequences suffer, it’s from too standardized a setting (the innovative school where quirky folk of all kinds learn to develop their remarkable abilities). Binti’s Earth is more surprising and more complex, precisely because Earth is, for Binti, the Himba homeland. Himba tradition pervades Binti’s experiences. It drives crucial points of conflict. Family is crucial, and Okorafor never shies away from it, refusing to let Binti be an orphaned free-agent in a universe of ahistorical difference.

Because this book collects four stories into a single volume, the resulting work doesn’t move with the expected patterns of a novel. Three novellas and a short story bump elbows in the cumulative 350 pages. Each has its own pace and expectations. These are not unified tales moving to a single climax. Rather, they are pieces of a young life (Binti ages only two years in the course of the book). She grows and changes as she reaches adulthood, but without the narrative sequence long-ingrained in western science fiction.

Binti’s age shapes the stories as well. Though they are not conventional young adult fiction, Okorafor’s novellas have unmistakable young adult elements of coming of age, transformation, hesitant sexuality, friendship forging, and the negotiation of independence. On Oomza, those elements too easily become formulaic. On Earth, Binti’s process of becoming is startling and vivid.

Okorafor’s future world, built out of real cultures and fully realized characters, should establish a new standard for science fiction in the 21st century.