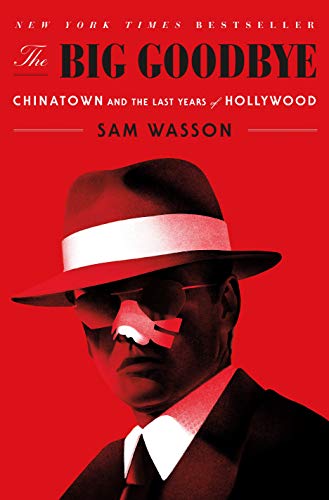

The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood

Sam Wasson’s biography of Bob Fosse was an engrossing portrait of a complex artist and man. It was also a fabulous read, so fast-paced that it felt like having a three-week affair with Fosse. The chapters, year by year sardonically counted down to Fosse’s death, all along, bringing the sharpest focus on the dance and theater world that Fosse thrived in.

Wasson is even more ambitious, and perhaps too narratively stylized, in his latest book The Big Goodbye, an exposé chronicling Hollywood in the ’70s and the project that brought the four ego-driven players—producer Robert Evans, director Roman Polanski, screenwriter Robert Towne, and superstar Jack Nicholson—to make the modern film noir classic Chinatown.

The quartet was trying to override industry hubris as the studios were being bought out by corporations who knew nothing about the art form except the bottom line.

After Evans hit big as producer of the low-budget film Alfie in the late ’60s, starring an unknown Michael Caine, he was scouted by a Gulf-Western Co. exec to be head of production at Paramount Pictures.

Director Roman Polanski was an internationally acclaimed filmmaker who also just had his biggest hit in the US directing Rosemary’s Baby, and was building a new life in Hollywood with actress Sharon Tate. Evans coaxed him out of seclusion in Europe after the murder of Sharon Tate and their unborn child by the Manson family.

Screenwriter Robert Towne was script doctor on the Godfather, which Evans produced. Towne conceived private detective Jake Gittes for Nicholson, his lifelong friend, who was reaching the crest of his career, after a string of hit movies including Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, and The Last Detail.

Towne’s book laces in such cinematic prose devises and the hothouse atmospherics of ’30s crime fiction of Chandler and Dashell Hammett and some gossipy tangents that should have ended up on the cutting room floor.

Chinatown is less a place in L.A. but more represents the decay of the Hollywood culture of the era, in part a hippie hangover, the 30-something coke fueled new execs taking over for corporate dinosaurs and lost romanticism of America as reflected on screen.

Polanski kept to himself as he was still struggling to piece together his life after losing Sharon and stayed focused, continuing to streamline Towne’s meandering style. Evans was also pushing for cuts behind Towne’s back. Wasson writes about Polanski with sensitivity and revisits his harrowing childhood: losing both of his parents in the Holocaust and the shattering experience of finding out over the phone in London that his wife and unborn child had been brutally murdered in his home in Hollywood.

Wasson spends a lot of time describing Towne’s troubling creative process and reveals how much he leaned on his script from fixer Bill Taylor, who repeatedly saved Towne without taking credit. The first complete draft was over 300 pages and what Evans and Polanski saw as basically indecipherable for a commercial film. Plus, it had a completely unsatisfying ending.

The heart of the book deftly describes the Polanski’s methods as a hands-on director and the artistic vision of the four main players that veer from simpatico to a test of wills. And some thrilling prose re-enactments from the actors’ perspective—notably Chinatown’s climactic scene (“She’s my sister, she’s my daughter”) between Nicholson and Faye Dunaway.

Ten days before the film’s premiere, Evans realized that the score, chosen by Polanski, was sinking the film and that the cinematography was too bright. He had to go behind Polanski’s back, in post-production, to give it a classic film-noir sound and look. He had to finesse getting veteran film composer Jerry Goldsmith to write a new score and to record it in 48 hours, just days before the film was to premiere in Hollywood to colleagues and critics.

The buzz at the screening was that it was a failure. But two of the most influential critics of the time hailed it as nothing less than a new Hollywood masterpiece. Within weeks it was one of the top box office draws, and it picked up 11 Oscar nominations.

Wasson’s four main bio tracks seem to pull him in too many directions and sabotages the flow of the book. Wasson’s overreaching style aims to evoke the cynical and romantic atmosphere achieved in the movie, not to mention its dark poetic mystique.