Beast in the Apartment

“This collection offers the riches of a mature poet’s reflections on life and death, which cannot help but enrich our own lives as well.”

“These poems relish the carnality of youth.”

All writing is translation of a sort, the writer transmuting the stuff of the world and of literature into something at once new and old.

As a respected translator of Chinese verse, Tony Barnstone is practiced at this art and has found his own way of enacting it in his new collection Beast in the Apartment.

Barnstone is well aware of the play of resemblance and difference both translation and writing one’s own poems implies and celebrates this in his poems, sagely noting that “everything is shaped like something else/and that’s how we know what it is” (“Shapely”).

The poems overflow with sly allusions, reflections, and skewed resemblance to other poets and their canonical works, from Homer to Yeats, Blake, and Dylan Thomas.

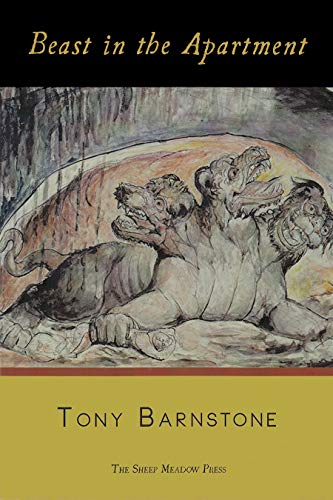

As a cue to this underlying thread, the book’s cover features a prominent instance of such transmutation: an etching by William Blake of Cerebrus, the three-headed hellhound of Classical lore. This is one of Blake’s illustrations of Dante’s Inferno, which itself transmutes earlier classical works and relies upon readers to recognize that fact.

Like Blake and Dante, Barnstone takes these references as his patrimony, alongside a certain scuffed gold watch from Istanbul his mother gives him, and studies it.

Though he desires, like a curious child, only to open this watch as one might shuck an oyster, to find the pearl (or Pearlman) of its origin, his efforts are foiled.

The object is too solidly made, and “[the] latch/ eludes me, though I close my eyes and feel/it shudder in my hand” (“A Watch From Istanbul”).

Yet even if he despairs of emulating the master craftsman who made this “strange/interior of stars and jewels and steel”(“Watchworks”), Barnstone knows his craft.

The book’s five sections are composed of interlinked poems, many of them sonnets, that echo and invert the lines of previous poems in the section in a way sometimes reminiscent of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience.

Take for instance the paired sonnets, “Die” and “Live,” which appear in the book’s second section, “All Fall Down.”

Though the title of “Die” seems to promise a bleak treatment of its subject matter, mortality, the poem turns out to be almost silly, a childlike glimpse of a loss the speaker only half understands.

It is only in the paradoxically titled “Live,” which we might expect to offer a more optimistic and hopeful view, when the awful permanence of this loss breaks through.

This is made still more horrifying by the fact that the poem’s speaker seems to become a sort of midwife of death, leading the poem’s addressee

“gently into that good night.”

Though the poem’s last line echoes Thomas’, it inverts the original’s meaning, for this speaker does not “rage against the dying of the light,” as the earlier poem’s speaker had, but in fact, advises the addressee to “[come] with me gently into that good night.”

It is not only his literary heritage that Barnstone investigates here, but his personal one as well. For in this collection, Barnstone registers his response to the experience of mid-life, retrieving his former self in all of its incarnations.

Knowing his own mortality only too well, the poet endeavors to seize what is left from life before its inevitable end. As he tells us in “Why I’m Not a Carpenter,” “since making is what I have,/ I make what I can out of this long unmaking.”

His way of doing that is to examine moments of passion in his past. These poems relish the carnality of youth.

For although the writer acknowledges that “I’ll be out of air one day/out of sex and poetry, that one day the holy/engine that keeps my body pneumatic/will shudder off” (“The Buried Buddha”), he relives these experiences in the act of fashioning them into words.

In the poems of this volume, particularly those in the first sections, he worships at the shrine of women’s bodies, a parade of partners whom he recalls with affection, witnesses the turning wheel of fortune in his own and others’ lives, and arrives at last at a kind of acceptance.

The beast in the apartment is but “a paper lion” and the kisses one delivers in a poem, like the Marvellian sonnet that makes up one unnamed part of “Rota Fortuna” are paper as well. But for all that, they are well made and worth savoring.

This collection offers the riches of a mature poet’s reflections on life and death, which cannot help but enrich our own lives as well.