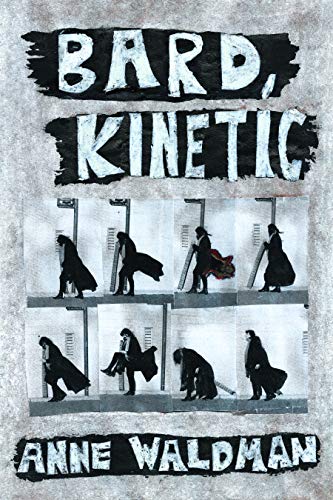

Bard, Kinetic

Black History Month has arrived once again, right on schedule. Readers eager to find and savor signs of Black history and Black culture in Anne Waldman's Bard, Kinetic will not likely be disappointed.

The author begins her story with a memory of herself sitting on the lap of folk singer Lead Belly when she was a child growing up in a family of bohemian New Yorkers.

Waldman also prefaces chapter one with the lyrics to Lead Belly's classic "By and by when the morning comes," which might be called her theme song, or at least one of them.

Lead Belly sang, "We're in the same boat brother." Waldman would probably add the word "sister" and sing, "We're in the same boat, brother and sister."

After Lead Belly makes a cameo appearance Waldman goes on to write about Amiri Baraka (formerly Le Roi Jones, and to call him "plangent messenger/ good dark angel."

She also mentions in passing Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale, African novelist Chinua Achebe, and singers/ songwriters Odetta and Nina Simone. Waldman calls ours a "mixed-race world," and invites a "reemergence of abolitionism as a political ethic, as the leading edge of utopian visions."

Is Bard, Kinetic an autobiography or a memoir? Waldman doesn't say, and neither does her publisher Coffee House Press, which has put into print four anthologies she has edited or co-edited. Coffee House does call the book "nonfiction."

If autobiography aims for inclusivity and memoir for a slice of a life then this book might rightly be called memoir. Clearly there are omissions about Waldman's love life, marriage, and romantic and literary partnerships.

Poetry and poets are front and center here, as they should be. If Waldman is to be remembered in years to come—she's now in her late 70s—she will surely be remembered as the author of five books of poetry and her infamous poem "Fast Speaking Woman," which includes the lines “I’m a jungle woman/I’m a tundra woman/ I’m the lady in the lake/I’m the lady in the sand,” and which is often included in anthologies of Beat literature.

Waldman writes as fast as she speaks, doesn't miss a beat ,and keeps going with kinetic energy from start to finish. Along the way she offers her reflections on William S. Burroughs, Etel Adnan, Joanna Kyger, John Ashbury, and others, careful not to exclude or to play favorites.

Sometimes she seems to be name dropping. Sometimes whole passages and whole pages are filled with only names. That's to be expected. She has known nearly everyone in the poetry world in the USA since the 1960s.

Bard, Kinetic would serve as a useful and inspiring text in a college class on poetry and poetics. In addition to the poems that are sprinkled generously throughout the book, there's a substantial bibliography that points readers toward Buddhism, dance, protest politics, Bob Dylan, and Jacques Derrida.

A female trickster, an earth mother, and a loyal sister, she celebrates the company of friends who sit "around a fire telling stories—a primordial ritual."

As a model critic, she takes on some of Burroughs' "crackpot ideas" and his "misogynistic statements" and adds "they have never distracted me from the mastery and deep power of his cinematic cuts and pastings."

Fittingly, Waldman includes many of her own poems, which help to ballast, electrify, and launch the book. The first poem, "Stepping Back," begins "I notice the night." The last, "July 4," which was written July 4, 2022, ends with four lines in italics that read like a direct invitation to readers to heed the poet's advice: "let fate/ crack an egg/ in the hat/ your only duty is to pray . . ."