Artists' Lives

This book collects articles and essays written by Michael Peppiatt, one of Europe’s leading art critics, across the span of his career. He began writing about art in 1966 when he was a student at Cambridge University. The most recent piece in the collection, and the longest, an essay comparing the work and lives of Francis Bacon and Alberto Giacometti, was published in 2018. In between, Peppiatt scans the landscape of modern European painting and sculpture, giving us sketches of notable figures as diverse as the Belgian Henri Michaux and the British painter Lucien Freud.

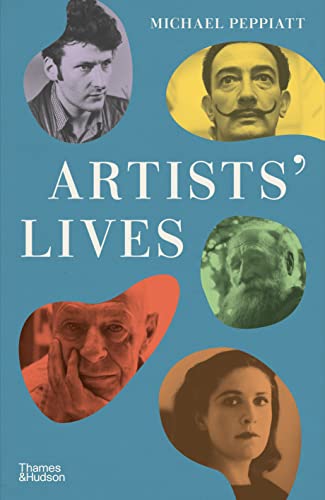

Peppiatt’s taste runs to artists who work in the figurative tradition, and who in their art confront the distortions of the human spirit caused by the cataclysmic events of the 20th century. Surrealists such as Salvador Dalí and Dora Marr are discussed, as well as professed “realists”—Bacon, Freud, Giacometti. Bacon and Giacometti and their relationships with other artists are frequent subjects. Peppiatt has devoted longer works to both of these artists, who for him became touchstones of the contemporary ethos by virtue of their engagement with suffering and despair.

Peppiatt is drawn to visual artists who also produce literature or who have been profoundly influenced by writers. Van Gogh’s letters stand out as both a personal record of his struggles and a declaration of his artistic credo, his way of looking at and rendering reality. Joan Miró, who illustrated works of literature, regarded painting and poetry as equivalent ways of apprehending reality. Michaux was both a painter and a poet, and Peppiatt argues that Michaux’s painting is commensurate with his poetry, for which he received greater notice.

Giacometti had numerous friendships with writers with whom he shared both artistic inclinations and philosophical attitudes. For a time he belonged to the circle of surrealists led by André Breton. After World War II Sartre wrote an essay about Giacometti that linked his work to existentialism and placed him on the cultural map of Europe. Giacometti also had a personal relationship with Samuel Beckett. Both men enjoyed visiting brothels and taking long nocturnal walks together through the streets of Paris. In 1961, Giacometti designed the set for a staging of Waiting for Godot at the Odeon Theater in Paris.

Some articles in Artists’ Lives profile not the artists themselves but their muses, companions, supporters, and critics. Dora Marr is remembered for her own work as a surrealist photographer as well as her stormy relationship with Picasso. Alice Bellamy-Rewald, who formed friendships with Picasso, Bacon, and Giacometti, wrote art reviews and was a fixture of the art scene in both Paris and, later, New York. John Richardson wrote a biography of Picasso and lived for many years as the companion of the wealthy and highly opinionated collector Douglas Cooper.

The reader of Artists’ Lives is taken on a stroll through a gallery of prominent 20th century European artists. Peppiatt knew many of these artists, curated exhibitions of their work, and socialized with them. He was especially attached to Francis Bacon, subject of his very first student article. Bacon helped him with his career, giving him entrée into the higher echelons of the art scene in Paris, where Peppiatt moved in 1966 and remained for 30 years. He writes discerningly about the artists who interest him, and deepens our understanding of their work by revealing connections between who they were and what they made. Most of these artists had experienced suffering in one form or another, and suffering suffuses their work.

Readers, especially those not familiar with the work of some of the artists Peppiatt treats us to, might be better positioned to appreciate the author’s commentary if Artists’ Lives had included reproductions of the work by the men and women under discussion. As it is, we are left to be content with black and white photographs of the artists themselves. It’s also notable that no American artists are included in a book being marketed to the American reader.