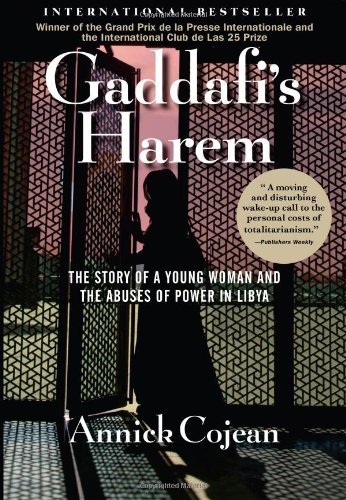

Gaddafi's Harem: The Story of a Young Woman and the Abuses of Power in Libya

Annick Cojean documents certain abuses of power during the Gaddafi regime in Libya—a period of more than 40 years. Assigned by LeMonde to write about the role of women during the Libyan Revolution of 2011, she discovered a deeper story that drew her back to the country again and again.

During his regime, Muammar Gaddafi purported to be a protector of women. Yet within the confines of his many dwellings he subjected thousands of young women to sexual servitude, a place from which they dared not escape nor speak out. In a country where sex outside of marriage is illegal and rape is taboo, speaking about these injustices harms not only the victim, but brings dishonor to her family.

Ms. Cojean typifies this dilemma by relating the story of one young girl: Soraya. She relates that Soraya refused to embellish or go beyond anything about which she was unsure. There are some subtle nuances that suffer in translation (i.e. “She (Soraya) doesn’t wish to be credible, she wants to be believed.”) from French to English, but Ms. Cojean’s investigation goes beyond one woman’s story.

As a student, age 15, Soraya was honored to present flowers to Gaddafi when he visited her school. Shortly afterward, she was taken from her family home and held captive for seven years in Gaddafi’s compound. Protest by family members was unthinkable.

While in captivity, women were forced to submit not only to perverted sexual acts, but also to drugs, alcohol, and tobacco. Days became nights and vice versa as young women were summoned at all hours, sometimes returning to their quarters beaten and bloodied, as well as suffering from myriad other indignities. Soraya remains a heavy smoker and deeply scarred in other ways, even after liberation. Soraya’s family will always be tainted by the shame of her experience.

Soraya relates seven years of relentless abuse with one brief escape when her father was able to get her to Paris, risking the life of the entire family and of the relative who took her in. It is puzzling that she chose to return to Libya. A relative in Paris attributes this to her immaturity, her total lack of discipline, years of a drugged existence, and no ability to speak the language or navigate adult life.

Equally puzzling is that upon her return she avoided the fate of many women who were brought back from escape and publicly humiliated (heads shaved) then executed. Other women, using false names corroborate her story.

The second half of the book details the author’s further investigation. The courage on everyone’s part is remarkable. The sheer weight of the repeated subject matter tends to make the book bog down in spots, rendering it difficult to read.

But the message is consistent.

While the focus is on the abuse of power related to women, a link to the larger story and the ultimate revolution that toppled the regime would have provided readers with additional background.

The revolution in Libya came to an end with the death of Gaddafi in 2011. In February 2013 women gathered in the streets of Tripoli with signs that read: “Never Again.” Ms Cojean’s book appeared on placards in French and Arabic. The silence of 42 years was broken, but with much resistance from people who felt it best to bury the entire issue. Why bring shame to the country? Why dishonor males?

Nonetheless, following the revolution, according to the author, women’s lives have changed.

“Their participation in the revolution had been so massive that they had helped to give it legitimacy . . . They couldn’t be kept out of it anymore . . . The women have faced fear, risks and responsibilities. In the absence of men, they were obliged to come out of the homes where they are frequently confined, and they have started to enjoy becoming active members of society. . .” We have rights. And we’ll be heard!

Gaddafi’s Harem now joins the burgeoning body of literature on human trafficking, exploitation of women, and the abuses of power relating to women. The truth of this ugly reality cannot be silenced, but another question remains unanswered: Can it be stopped?

The author is an experienced reporter and winner of the 1996 Prix Albert Londres, the French equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize. For this work, Ms. Cojean was awarded the Grand Prix de la Presse Internationale and International Club de Las 25 Prize (for investigative journalism).

It will be years before the world will know how Libya has reinvented itself. The country has recently begun prosecutions related to crimes committed by top Gaddafi officials, including Gaddafi’s own son.