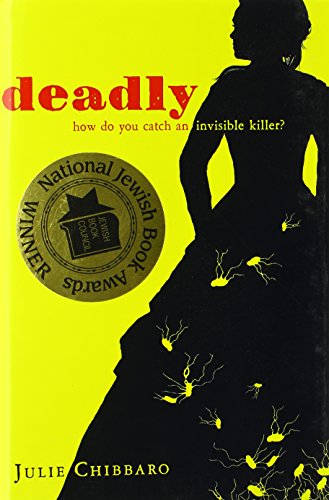

Deadly

It’s 1906, and tenement-dwelling 16-year-old Prudence is a brainy loner, grieving over her brother’s death from infection and her father’s disappearance in the Spanish-American war.

Lessons at Mrs. Browning’s School for Girls, meant to prepare her for social advancement as a secretary, fail to inspire her. Having assisted her midwife mother at many difficult births among the poor, Prudence wants to find a job doing something important, preferably something to help fight the death and disease she sees all around her. She can hardly believe her luck when she lands a job as assistant to New York State’s head epidemiologist, George Soper.

Typhoid fever can occur in clusters even among the well-to-do, and Prudence’s careful record-keeping and analysis help Mr. Soper pinpoint the cause of an outbreak on Long Island. There, Prudence and her chief encounter Mary Mallon, the furiously defensive Irish cook whom history knows as Typhoid Mary. Prudence suffers qualms of conscience over the methods the health department uses to track down and detain the immigrant cook, but at the same time she blossoms under the possibility of finding a new identity for herself as a woman scientist.

This is a book about finding identity and purpose in work. Author Julie Chibbaro recognizes that for a poor, lower class young woman to make her way in the traditionally male fields of science and medicine, mentors are critical. Prudence finds her first mentor in the work-obsessed Mr. Soper, the only male around to take her intellect seriously. In a convincing touch, Prudence develops a secret crush on her chief and wants nothing more than to be around him, even when his tactics of investigation strike her as unscrupulous. Through Mr. Soper she meets a female physician, Dr. Sara Baker, who urges her to steer away from matters of the heart and pursue the study of medicine instead. “You must learn to stay neutral,” Dr. Baker advises. “Save your passion for yourself and the knowledge you must acquire.”

Ms. Chibbaro lets Prudence tell her story through short journal entries that show her growing sense of commitment to science, her struggles against the disapproval of the women around her, and her stirrings of romantic feelings. Scattered throughout the journal are careful biological drawings that we assume are Prudence’s own.

Prudence’s language is balanced and formal, as far as possible from the chatty language of modern teenage chick-lit. Along with the language, details of transportation and street life give a strong sense of place and time to the story. The state of a young girl’s scientific knowledge is also accurately portrayed: at one point, Prudence muses at the strange idea that it takes “many hundreds” of cells to make a person. Both Mr. Soper and Dr. Baker are historical characters, and the novel’s plot keeps reasonably close to the known history of Typhoid Mary.

The book’s title and flap copy may lead young readers to expect a mystery, or at least a story where Prudence plays a more central role than she does in uncovering the truth. Readers looking for the conventional twists and turns of mystery will be disappointed; the solution appears without much suspense in the first half of the book. Others expecting a conventional romance will also be disappointed by Prudence’s choice of love object and her eventual decision to move beyond it. This book isn’t a romance or a mystery; it’s a voyage of self-discovery.

Any reader who has occasionally felt isolated by her commitment to learning or by her aspirations to more than social success will find herself rooting for a sister spirit in Prudence. This book will be especially welcome to girls with an interest in science, medicine, history, or just in reading about a strong, honest female protagonist.